What is a sketchbook?

20th November, 2022A sketchbook is a creative document that contains both written and visual material. It may include teacher-guided sketchbook assignments or self-directed investigations. A sketchbook helps you to think through the stages of the creative process: researching, brainstorming, experimenting, testing, analyzing, and refining compositions. It is a place to document your journey towards a final solution, providing depth and backstory to the accompanying artwork. A sketchbook is an important part of many visual art courses.

“A sketchbook is a way to process raw information.”

Sketchbooks allow you to quickly jot down ideas as you have them. So whether you are in the air, taking a walk in the park or having lunch at a cafe, the sketchbook allows you to record your ideas. After all, inspiration can strike at just about any time.What should a sketchbook contain? (A sketchbook checklist)

Many high school art projects have flexible, open-ended requirements. The recommendations below explain what is typically expected in a high-quality sketchbook.

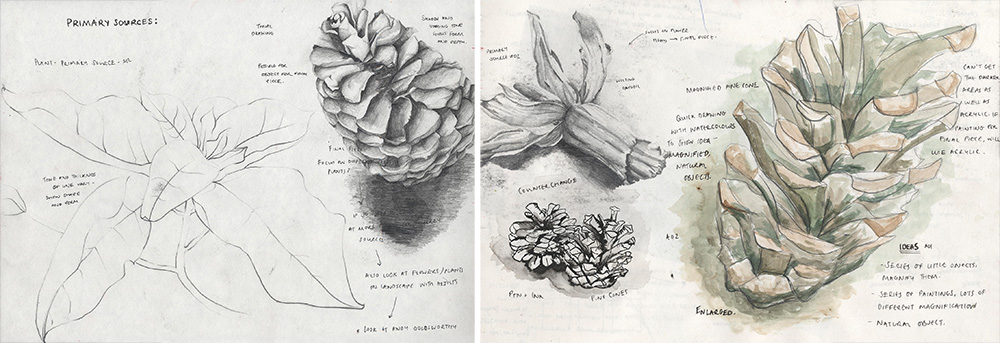

First-hand engagement with the subject matter

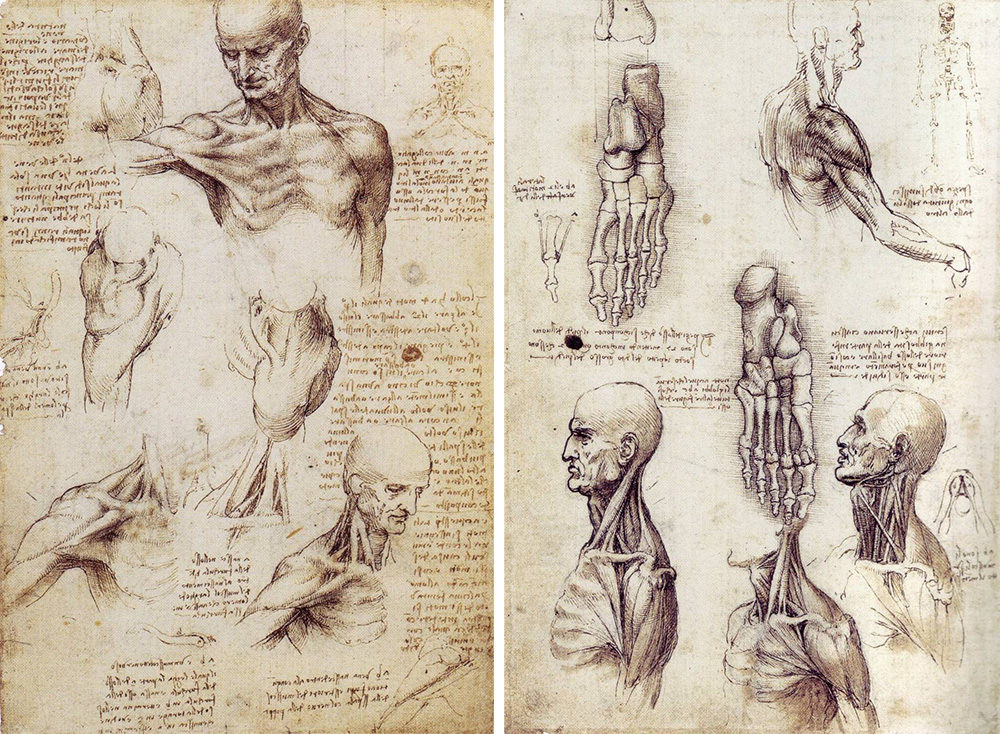

It is essential to demonstrate a clear personal connection to the theme/s explored in your sketchbook. You can do this by drawing from first-hand observation; working from original photographs; documenting personal visits to galleries, historic places, museums, or design sites; and explaining the personal context surrounding your work (how the work is relevant to you and your life).

A project based solely on secondary sources (such as images from the internet, books, or magazines) is typically frowned upon by examiners and may lead to superficial work, a lack of engagement, and plagiarism.

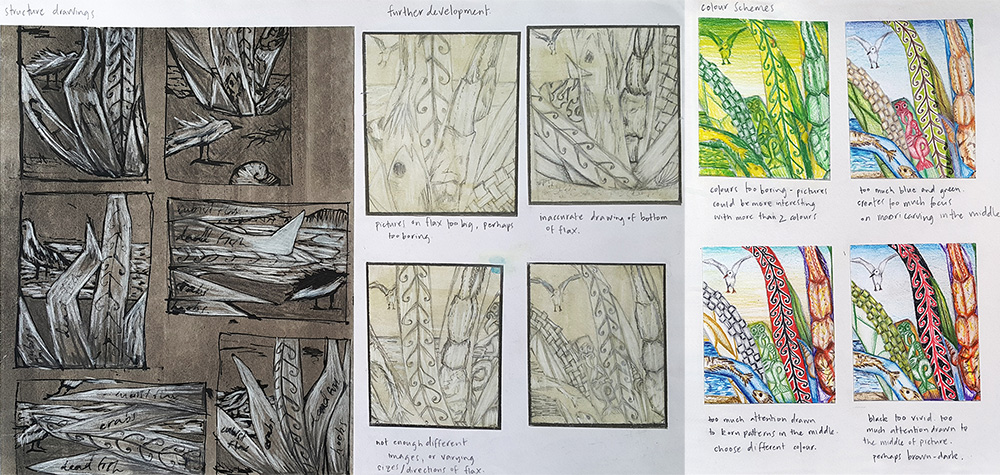

Exploration of composition, visual elements, and design principles

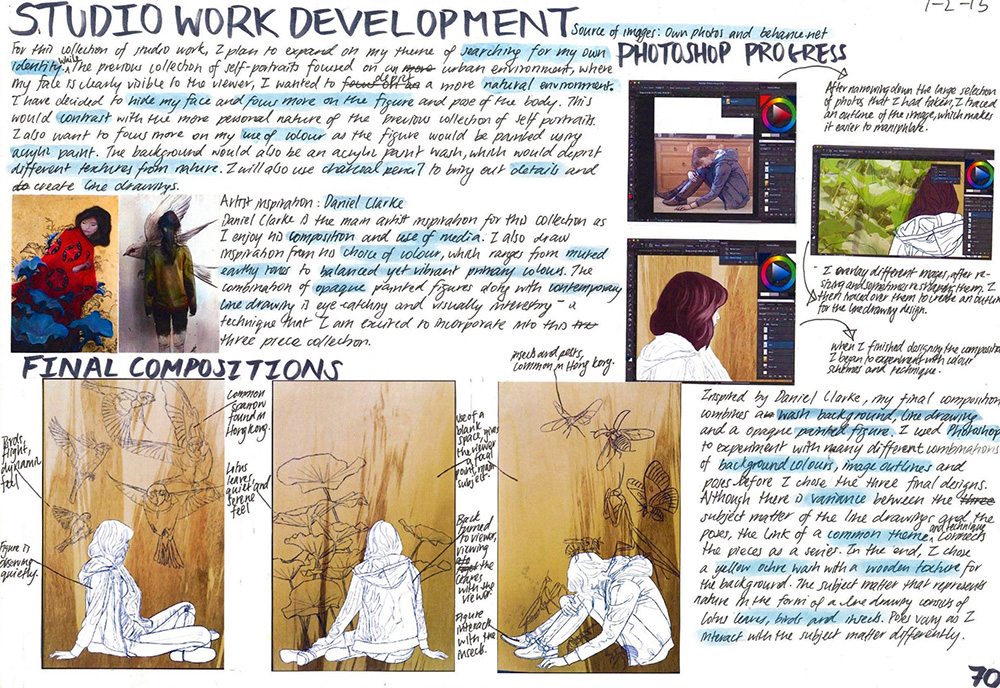

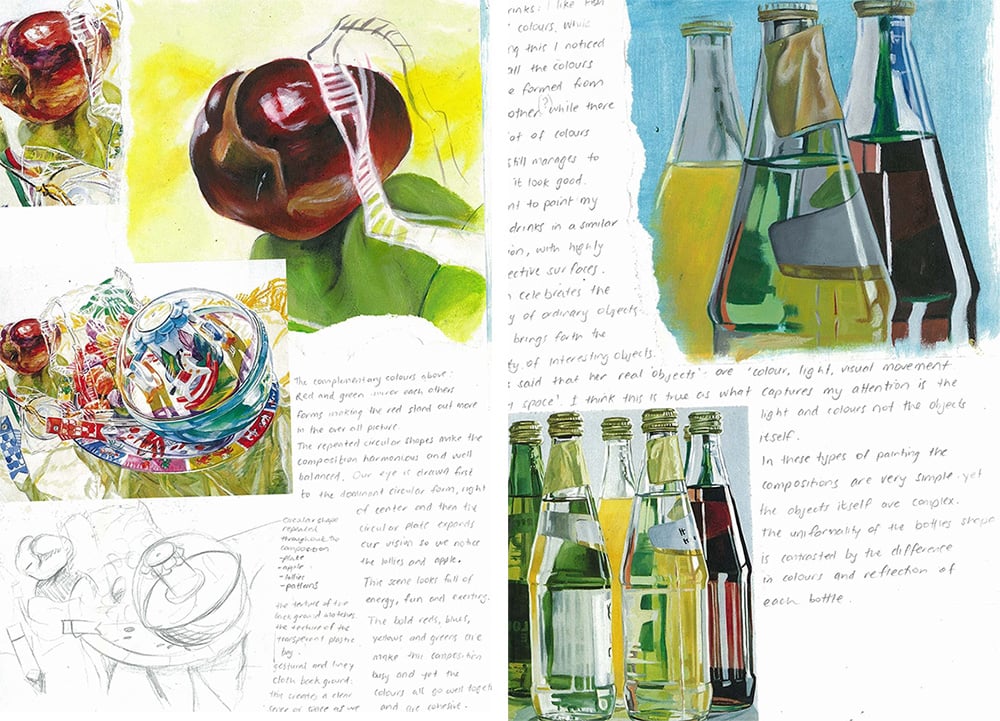

An important role of the sketchbook is to aid the planning and refining of larger artworks. This might include composition studies, thumbnail sketches, or layout drawings (exploring format, scale, enlargement, cropping, proportion, viewpoint, perspective, texture, surface, color, line, shape, form, space, and so on); design ideas; photographs of conceptual models or mock-ups; storyboards; photographic contact sheets; analysis of accompanying portfolio work; and many other forms of visual thinking.

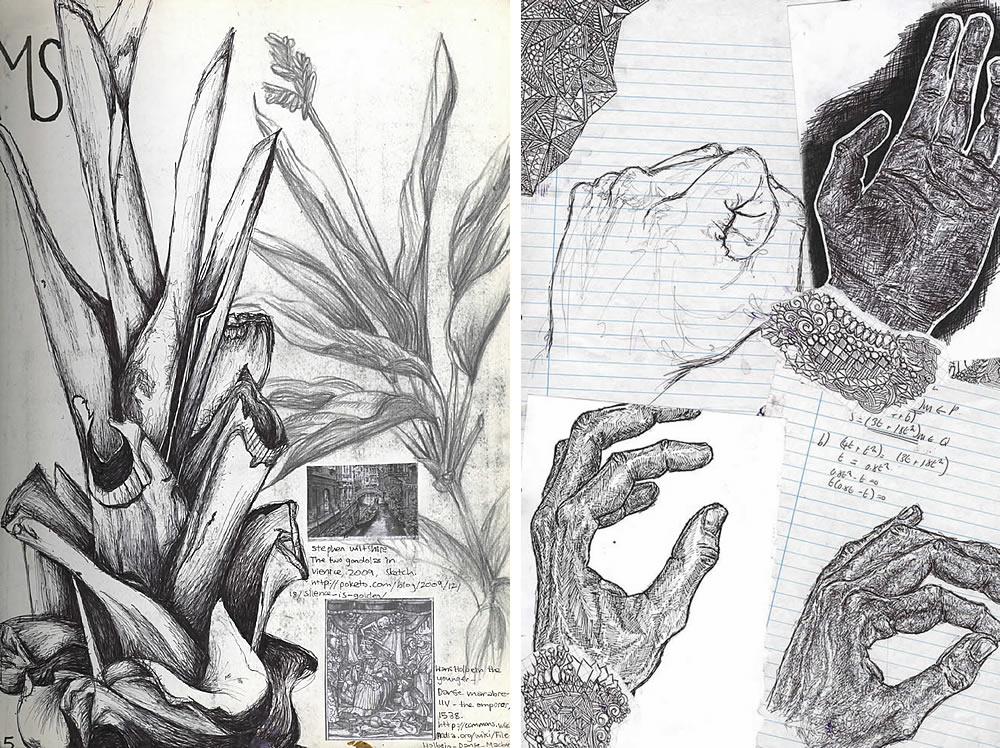

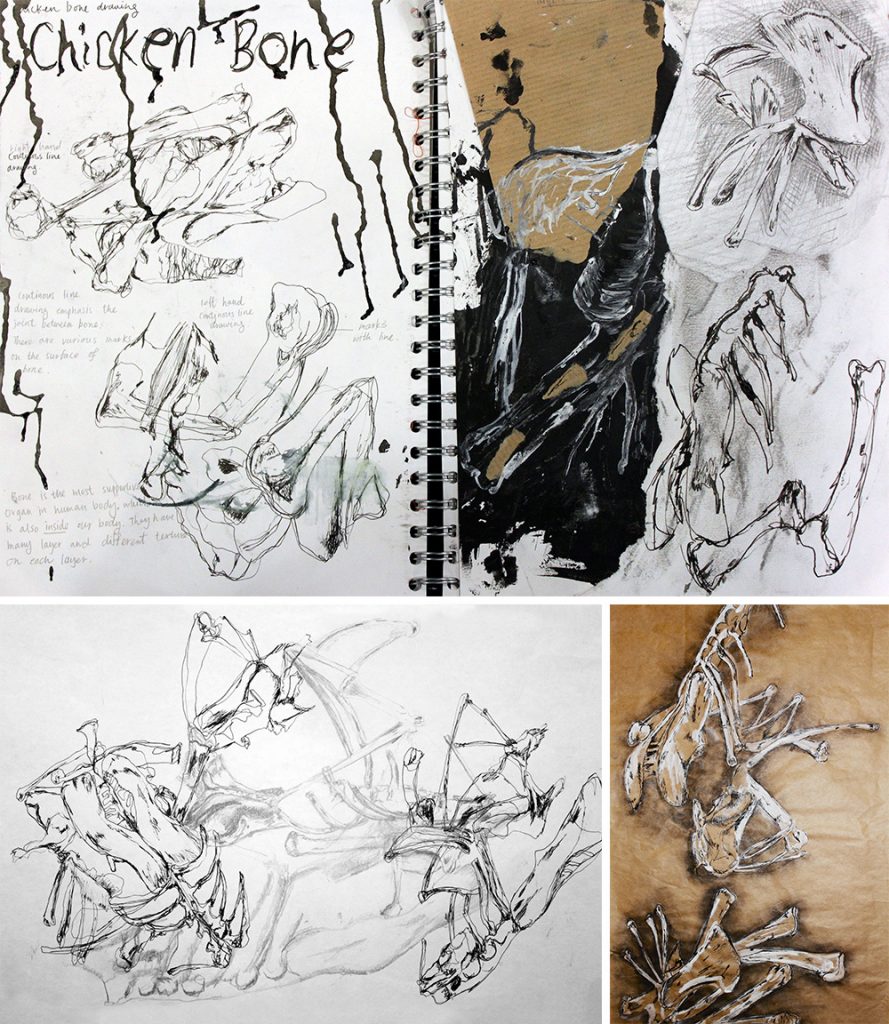

Original drawings, paintings, prints, photographs, or designs

Fill your sketchbook with original visual material—particularly work that is exploratory, incomplete, and experimental (as opposed to finished artwork). Visual material should support the theme of the project, rather than depict a random collection of unrelated subject matter.

A wide range of media and materials

Your sketchbook should contain a wide range of media and materials, as appropriate for the project and area of specialty. Include photographs of any three-dimensional exploration. A broad list of possible media and materials is listed below:

Drawing and painting surfaces: colored and textured papers of varying weights, such as tissue paper, watercolor paper, newsprint, or cartridge; cardboard; transparent sheets, plastic overlays, or tracing paper; discarded wallpaper, patterned paper, or printed sheets; photographic paper or other specialized printing papers; painted or prepared grounds; masking tape or other adhesive surfaces; collaged materials; dried textures created with acrylic pastes or compounds; canvas, hessian, or other fabrics; other appropriated items. (See more examples of drawing and painting surfaces in our four-part Creative Use of Media series for high school art students.)

Drawing and painting media: graphite pencil; colored pencil; ballpoint pen; ink pen; calligraphy pen; marker pen; chalk; charcoal; crayon; pastel; drawing ink; printing ink; natural or manmade dye, such as from commercial pigments, walnut skins, coffee stains, or food dye; gouache; watercolor; acrylic paint; oil paint; spray paint; house paint; shellac/varnish; fixative; wax; painting mediums, such as thinners, gel/gloss, glazes, drying retarders, textural pastes, or modelling compounds.

Threads and textiles: natural fibers, such as cotton, silk, flax, or raffia; wool and other animal hair, furs, or leather; synthetic threads, such as nylon, acrylic, or polyester; textiles of different weights, weaves, patterns, prints, or colors; upcycled fabric, including from non-traditional sources such as repurposed woven plastic bags; elastic; sewing threads; embroidery threads; string; rope; beads.

Sculptural materials: glues or adhesives; papier-mâché; salt dough; modelling clays or ceramics; feathers, bone, or other animal materials; food; seeds, leaves, cane, balsa, or other woods; sand, earth, pumice, rocks, or stone; wax; plaster; latex; Styrofoam; plastics; resin; concrete; fiberglass; wire, foil, or other metals; ice; light; other organic and manmade found materials.

Tools and technology: brushes; airbrushes; sponges; paint rollers; palette knives; craft knives; scissors; stencils; engravers; sandpaper; chisels, pliers, or other woodworking tools; metalworking tools; paper trimmers; pottery wheels; crochet hooks, needles, sewing machines, or overlockers; looms; traditional or digital cameras; darkroom equipment; kilns; printing presses; photocopiers; scanners; computer-aided design (CAD) software such as Adobe Photoshop, Adobe InDesign, or SketchUp Pro; computer-aided manufacture (CAM) equipment such as 3D printers and laser cutters.

A wide range of art-making techniques, processes, and practices

The techniques, processes, and practices explored in your sketchbook should be appropriate for the project and area of specialty. Try to use both traditional and contemporary approaches. These should be informed by the study of relevant artists and first-hand practical experimentation. Complex processes can be documented using diagrams, annotated screenshots, or photographs of work in progress (this can help to prove that the finished pieces are your own work). Don’t document every technique at every stage of production. This is a space-filling device that pushes out more relevant content.

Artist research

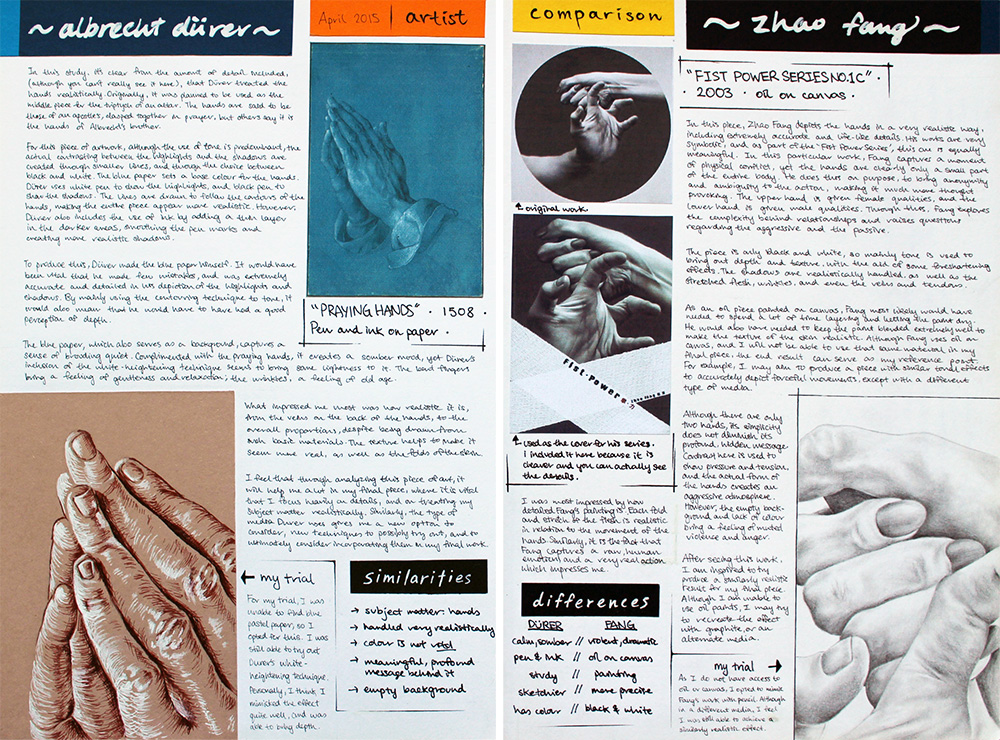

The sketchbook is an excellent place to document learning from the work of artists. This might include whole or partial copies of relevant artwork accompanied by critical analysis and practical experimentation where appropriate. Artists should be selected purposefully and offer valuable learning opportunities in their approach to subject-matter, composition, technique, or use of media. Aim to study the work of both historical and contemporary artists from a range of different cultures. Avoid bulking up the sketchbook with gallery pamphlets, fliers, brochures, or other printed material from secondary sources.

Sketchbook presentation tips

A high school sketchbook should be reminiscent of the kind of document that an artist or designer might create. It does not need to be overworked, perfect, or polished. The following tips provide broad guidance in terms of page layout and presentation style.

Keep it simple

Avoid intrusive lettering, elaborate front covers, decorative borders, over-the-top backgrounds, or unnecessary framing or mounting. Fold-out tabs add an interactive element but risk examiners missing work, so are best avoided.

Use small, legible handwriting—this way, any spelling or grammatical errors are less distracting. Write with graphite pencil or black, grey, or white pen.

Do not spend weeks dreaming up inventive layouts or researching presentation ideas on the internet. Focus on what matters: producing quality art and design work.

Your sketchbook can be a straightforward, ordered presentation of your work, research and insights: Let your images do the impressing. Overly designed pages can often take too long and be a distraction to the viewer.

Chris Francis, Senior Leader, Teacher of Art and Photography, St Peter’s Catholic School, Bournemouth, England

Use a consistent presentation style

Some students favor hard-edged, ‘cleaner’ presentation methods; others prefer a messier, gestural style. Neither is better than the other: both can be executed well. Jumping from one presentation style to another, however, may result in a submission that is distracting and disjointed.

Vary page layouts to create visual interest

Some sketchbook pages should have many illustrations, others a single artwork, and the remainder something in between. Vary the positioning of images and text on the page. Don’t be afraid of white space.

Order work so that it shows the development of ideas

Although a sketchbook is an informal, free-flowing document, it is important to remember that an examiner picks it up and ‘reads’ it in a short period of time. Structure the sketchbook in a way that reflects the overall development of your project.

Do not bulk up your sketchbook with weaker work

Weak work sets off alarm bells for an examiner, alerting them to be on the lookout for weaknesses elsewhere. This does not mean that anything ‘less than perfect’ should be discarded. Mistakes provide valuable learning opportunities and cues for how subsequent learning took place. However, you must discriminate. If an image is glaringly worse than others, consider improving or eliminating it. Seek your teacher’s guidance before removing any artwork; improving existing work is often much faster than starting afresh.

Craft the sketchbook with care

The sketchbook offers an opportunity to remind the examiner that you are a dedicated, hard-working student, and that you care about the subject. This does not mean you must cram your sketchbook with intense, labored work (sometimes an expressive two-minute charcoal drawing is all that is needed), but rather that the sketchbook should speak of your effort, commitment, and passion.

You may also be interested in reading How to annotate a sketchbook, which contains illustrated examples from high-achieving students around the world.

Sketchbook formats – options available

For convenience, most students select a sketchbook that is A4 (8.5 x 11 in) or A3 (11 x 17 in) in size. An A4 sketchbook fits in a schoolbag and is thus less likely to be lost or damaged during transit. An A3 sketchbook fits more work per page and provides space for larger artworks. If the sketchbook contains all preparatory material without any additional sheets of developmental work required, an A2 (17 x 22 in) sketchbook may be appropriate. Non-conventional sizes or electronic submissions may also be possible. Remember that format requirements are often set by an examination board, teacher, or school.

Regardless of the sketchbook size, it is best to work consistently in portrait or landscape orientation, rather than alternating from page to page. Consistent page orientation makes it easier for an examiner to flip through the sketchbook and view your work. Landscape orientation is preferable for electronic submissions, as this displays well on digital screens.

Four possible sketchbook formats are summarized on the following pages. These are just a few of the options available.

Pre-bound sketchbooks

Pre-bound sketchbooks should contain quality artist paper suitable for both wet and dry media. A minimal appearance is best: choose a sketchbook with a plain cover, without distracting logos or ornamentation. A spiral-bound book allows you to remove pages easily.

The main disadvantage of a pre-bound sketchbook is that it is difficult to work with wet media on several pages at once. (Moving quickly between pages saves time, aids the development of ideas, and facilitates connections between pieces.) Nonetheless, pre-bound sketchbooks are the most popular format due to their convenience and wide availability.

Refillable display books

Another popular presentation method is to store loose sheets of paper in a refillable display book. The plastic sleeves protect the work and reduce smudging from one page to another. This method is less daunting than using a pre-bound sketchbook, as there is no fear that each page must be ‘perfect’—pages can be removed, added, and re-ordered with ease. Creating a sketchbook from individual sheets also allows easy integration of different paper types, encouraging the use of a broad range of media. In addition, you can work on multiple pages at once without waiting for work to dry.

A disadvantage of this method is that loose sheets are more likely to become lost or damaged. The plastic sleeves also hinder the viewing of surface quality and texture, particularly if the sleeves become crumpled or dirty. For this reason, you may wish to change to a clean, non-reflective display book immediately before assessment.

Self-bound booklets

Many schools own a manual binding machine. This punches a series of holes along one side of a document so that a spiral binding can be inserted to hold the pages together. A clear plastic cover can be added to protect the work. Binding usually takes place once the submission is complete, with sketchbook pages stored as individual sheets of paper beforehand. Other binding methods are also possible if these allow the sketchbook to lie flat when open.

As with refillable display books, different paper types can be used, and working on more than one page at once is possible. Pages can also be removed, added, and re-ordered with ease.

This method is more time-consuming than others and is prone to user error (such as holes punched along the wrong side of an artwork). Nonetheless, it is an inexpensive way to create a high-quality, personalized sketchbook.

Digital sketchbooks

A digital sketchbook typically takes the form of an online portfolio created using a website design platform such as WordPress. A digital sketchbook relies on access to high-speed internet and an appropriate laptop, computer, or other device. Images, videos, and typed annotations are presented on website pages using hyperlinks, menus, and categories to organize content.

The primary advantage of an online portfolio is that you can include digital images, audio, and video footage with ease. Digital sketchbooks are growing in popularity, particularly for students who specialize in film, photography, and digital media.

If you opt for a digital sketchbook, make sure you have backup copies of files stored on a memory stick or cloud server (an automatic backup service, such as Dropbox, is recommended) with digital files stored in labeled folders on your device. It is also wise to print a copy of each online portfolio page. These printouts can be bound and submitted so that examiners have a physical copy in case of technological difficulties.

Before opting for a digital sketchbook, it is worth remembering that long hours online and the distraction of social media can affect mood and sleep, compromising your productivity and quality of work overall.

There are also benefits to keeping a traditional sketchbook alongside a digital portfolio. This helps verify the authenticity of your digital work, allows the spontaneous transfer of ideas by hand, and strengthens and consolidates your practical art-making techniques.

Why are sketchbooks so important in an artist’s journey?

1. They are a chronological record of your progress

If you ever feel unmotivated or need solid proof of your progress, you can look back to your old sketchbooks and see how far you’ve come. You can also study them in order to find patterns in your work, as well as your style evolution throughout the years.

2. They protect your work for you

If you are generally a disorganized person or simply a busy one, it is very easy to lose those sketches you create. Whether you are a professional artist or a hobbyist that finds joy in art, it is important that this work is protected and not lost.

3. They are portable

As artists it is important to have the tools we need handy at all times. Whether it’s a camera to take reference photos, a small notebook to jot ideas down, or an actual sketchbook, we need to be prepared when we are out and about. It’s important to keep in mind that drawing and painting from life is extremely important.

4. They provide us with an informal, no pressure way of exploring

Art, as in most things in life, it’s more about the journey than the destination. As artists we have to fall in love with the process of exploration and keeping a sketchbook is a great way to do that. It is through smaller studies that we discover ourselves as artists, the techniques we love most, what we excel at and what we must work on.

Sometimes a finished sketchbook is even more important than the finalized pieces we produce, as it displays all the work it took you to get to where you are today. Ignoring practice and going straight to the canvas isn’t going to get you anywhere.

5. They remind us to keep going

Sketchbooks remind us of unfinished work and it is waiting to be filled up with more ideas and arts.

What to put in a sketchbook?

- First-hand engagement with the subject matter

You should include evidence of a clear personal connection to the theme/s explored, such as original photographs; observational drawings; documented visits to design sites, historic places or museums; and explanations of the personal context surrounding the work. A project based solely upon secondary sources (such as images from the internet, books or magazines) may lead to a lack of personal engagement, plagiarism issues, and superficial, surface-deep work.

- Exploration of composition, visual elements, and design principles

An important role of the sketchbook is to aid the planning and refining of larger artworks. This might involve: composition studies, thumbnail sketches or layout drawings (exploring format, scale, enlargement, cropping, proportion, viewpoint, perspective, texture, surface, color, line, shape, form, space and so on); design ideas; photographs of conceptual models or mock-ups; storyboards; photographic contact sheets; analysis of accompanying portfolio work; and many other forms of visual thinking.

- Original drawings, paintings, prints, photographs, or designs

Fill the sketchbook with your own visual material – particularly that which is exploratory, incomplete and experimental (as opposed to finished illustrations). Images should support the theme of the project and should not depict a random collection of unrelated subject matter.